Propaganda, Terrorism, and Regime Change

A Brief History of Resistance to China's Belt and Road Initiative

Beijing’s most ambitious foreign policy venture is reshaping the global economic landscape—but not without resistance.

In 2013, during state visits to Kazakhstan and Indonesia, China’s new Chairman, Xi Jinping, unveiled what would become the centrepiece of his global vision: the Silk Road Economic Belt and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road—together known as the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). The names evoke the grandeur of ancient trade routes, but the vision is unmistakably modern: an ambitious plan to connect Asia, Africa, Europe, and beyond through infrastructure, investment, and economic integration, all under Chinese direction.

More than a decade later, the BRI has become one of the most consequential—and controversial—geopolitical projects of the 21st century. At its height, it promised to reshape global supply chains, spur development across the Global South, and elevate China's soft power. It was quickly smeared by the collective West as debt-trap diplomacy and has prompted broad-ranging strategic countermeasures from the West.

To understand what the BRI has become, one must first understand what it set out to be.

The Genesis: Ambition Meets Opportunity

The launch of the BRI came at a fortuitous time for China. Domestically, it represented an opportunity to redirect industrial overcapacity that was growing in its steel, cement, and construction sectors after years of infrastructure-driven growth. Financially, China had accumulated vast foreign currency reserves, much of which was sitting idly in U.S. Treasury bonds. The BRI offered an elegant solution to simultaneously export capital, excess capacity, and political influence.

Its strategic objectives were layered. On one level, it sought to deepen China’s economic ties with its neighbours and secure overland access to energy routes, bypassing vulnerable maritime chokepoints like the Strait of Malacca. It also aimed to bolster growth in China’s western provinces building on the back of China’s ‘Go-West’ development strategy by promoting cross-border trade, particularly with Central Asia. And on a grander scale, it was Beijing’s bid to redefine global norms around development, connectivity, and governance. A chance to create an alternative to dominant ‘rules-based order’ espoused by Washington.

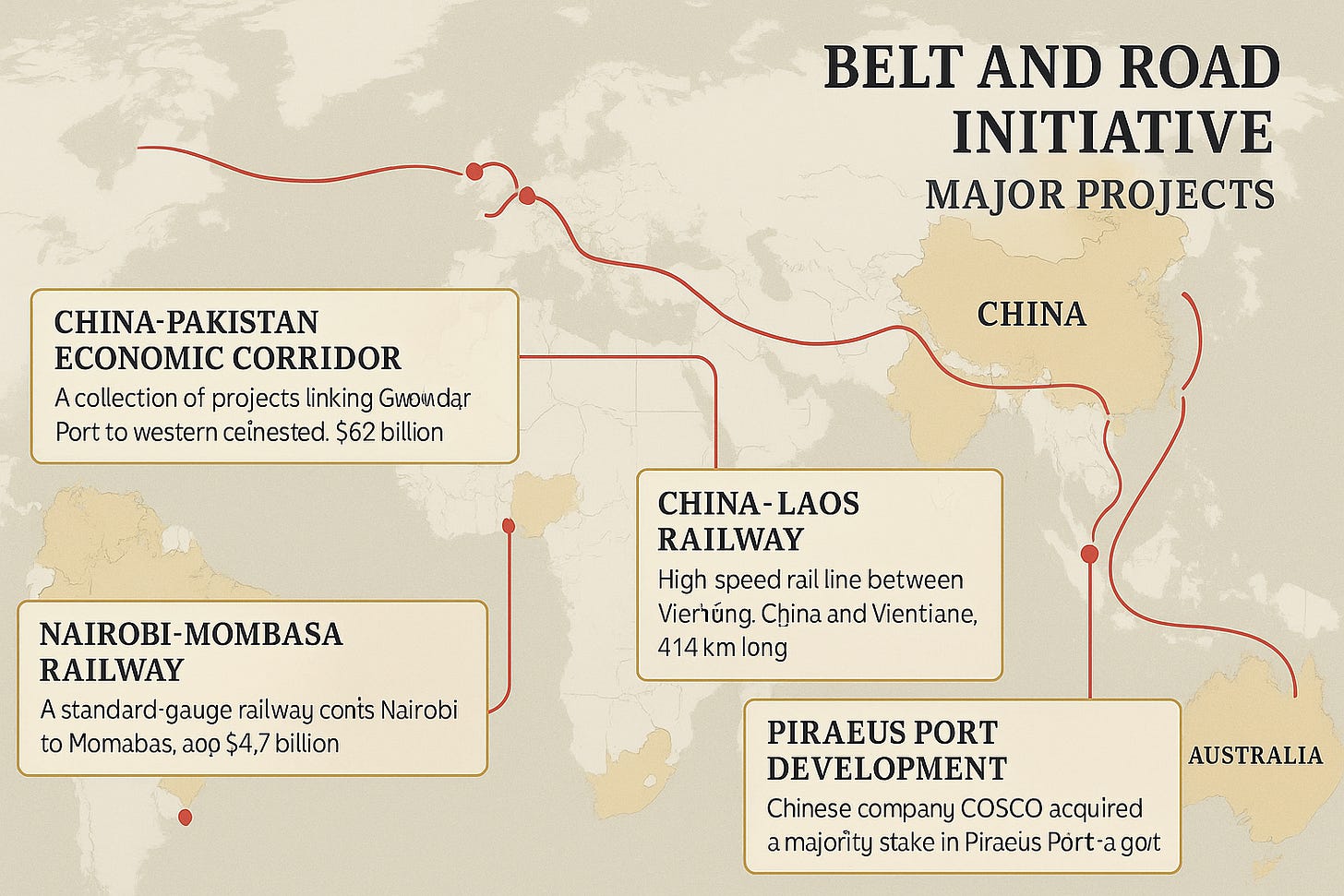

In the beginning objectives were left intentionally vague, open to interpretation and flexible in scope. This ambiguity was strategic. It allowed virtually any Chinese-financed or Chinese-built project abroad to be branded as part of the BRI. Highways in Kenya, ports in Greece, railways in Laos, power plants in Pakistan—all became links in what China called “a new era of globalization.”

The Expansion: Dollars, Deals, and Diplomacy

From 2014 to 2019, BRI projects multiplied fast. According to data from the China Global Investment Tracker, over 140 countries signed cooperation agreements, and cumulative investment topped USD1 trillion. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) such as China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) and PowerChina took the lead, backed by policy banks like the China Development Bank and the Export-Import (ExIm) Bank of China.

Much of the investment focused on transportation—railways, roads, ports, and airports—but also extended to energy, telecommunications, and even digital infrastructure. In some regions, BRI projects filled critical gaps. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), valued at over USD60 billion, funded everything from highways to coal plants to fibre-optic cables. In East Africa, Chinese firms helped build the Addis Ababa–Djibouti Railway, facilitating trade in a landlocked country long isolated from international markets.

But it wasn’t just about hard infrastructure. The BRI also had a diplomatic dimension. Forums, exhibitions, and think tanks flourished under the banner. The trappings of multilateralism—summits, memoranda, working groups—gave it the aura of a global consensus, even as China retained control over agenda.

For recipient governments, especially those in the Global South, the BRI offered a compelling proposition: funding with few strings attached, fast implementation, and the promise of economic transformation. In contrast to Western ‘aid’, which often came with a spider’s web of strings attached to neo-liberal governance models or commitments to open market, Chinese financing emphasized non-interference and pragmatism.

The Backlash: From Golden Era to Western Sponsored Containment and Strategic Pushback

As the scale of the BRI ballooned, so did concern in the West.

Western nations were quick to accuse China of using the initiative as a debt trap to tie Global South nations to Beijing.

Sri Lanka: The debt trap narrative begins

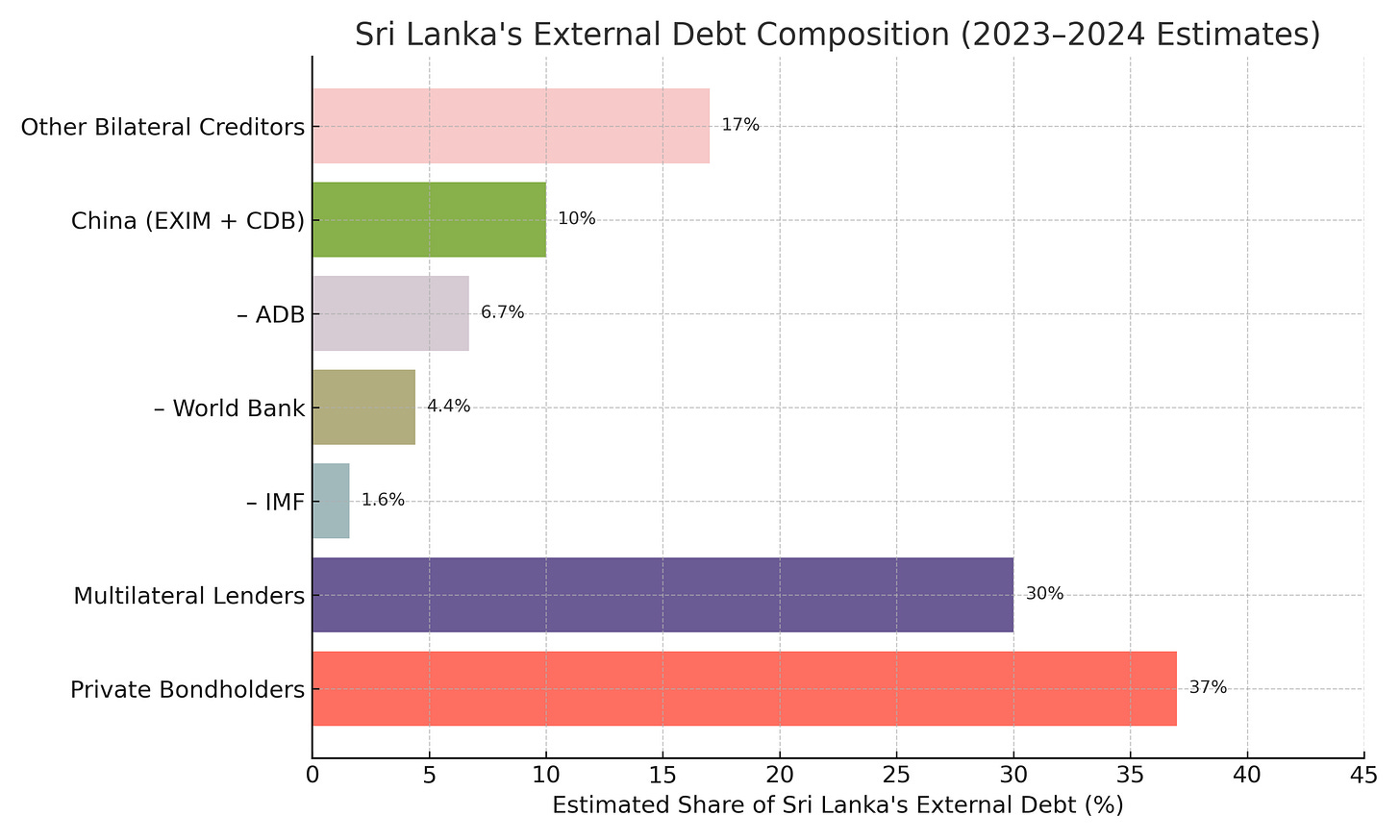

One of the most cited cases was Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port, which, unable to service its loans, was leased to a Chinese firm for 99 years in 2017. While the “debt trap diplomacy” narrative was repeated constantly in the Western media the reality is that China never held more than around 10 percent of Sri Lanka’s external debt and 26% of bilateral credit; while lenders like the IMF, World Bank (WB) and Asian Development Bank (ADB) hold around 30 percent with private bond holders making up the largest single category at around 37 percent.

Myanmar: Strategic Kyaukpyu port and oil pipeline

In Myanmar, Western support for Aung San Suu Kyi's NLD and sanctions following the military coup to remove her party from power have complicated China’s infrastructure goals.

The strategic Kyaukpyu port and oil pipeline—key to China’s Indian Ocean access goals—face significant resistance due to covert Western support for insurgencies in Rakhine State and anti-China sentiment stoked by foreign backed anti-government civil war actors that actively disrupt Chinese projects.

Malaysia: Freezing or cancelation of USD22 billion in Chinese infrastructure deals

In Malaysia, the ousting of pro-China PM Najib Razak in 2018 and his replacement by Mahathir Mohamad led to renegotiation and cancellation of Chinese infrastructure deals. Flagship BRI projects like the East Coast Rail Link were paused, then downsized with Mahathir parroting Western narratives, criticizing “debt-trap diplomacy,”.

Although ostensibly brought down by a domestic corruption scandal, there are clear fingerprints of a US regime change operation.

In 2016, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) launched a civil forfeiture case against Najib calling it the “largest kleptocracy case” in U.S. history. The DOJ’s pursuit of 1MDB assets embarrassed Najib globally and made his domestic position untenable.

Western media outlets like The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times played key roles in publicizing the corruption allegations driven by DOJ leaks and Western legal organizations and NGOS tied to George Soros’ Open Society Foundation helped to magnify the impact of the allegations.

Added to this, US diplomats frequently met with civil society leaders prior to the election and the National Endowment for Democracy (NED) provided funding to Malaysian NGOs critical of Najib.

While Najib’s fall was largely domestically driven by corruption, Western institutions played a key role in amplifying the fallout thereby facilitating a political climate that allowed a sharp pivot away from Beijing-aligned policy. This fit neatly the US strategy of constraining BRI expansion through a mix of lawfare, media pressure, and civil society leverage.

Pakistan & Baluchistan: Undermining the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC)

Whilst there is little official evidence of collusion between the US, Indian intelligence and the Gulf Monarchies in funding and coordinating Balochi separatist movements there is extensive open source and circumstantiation evidence.

In 2019 Saudi-owned Riyadh Daily featured an interview with Khalil Baloch of the Baloch National Movement, which openly legitimized attacks on Chinese and Pakistani targets. This has been widely interpreted as tacit support by Gulf elites for Baloch insurgency activity.

In addition, Saudi nationals of Baloch descent and Gulf-funded madrassas have reportedly funnelled cash and logistical support to militants to pressure China’s infrastructure projects in the region.

Support for the insurgency has led to persistent attacks on CPEC workers, slowed Gwadar port related progress and forced China to significantly increase its security footprint in Pakistan with military escorts and has raised risk premiums.

Greece: EU Efforts to Curtail Chinese Port Control

After COSCO acquired majority control of the Port of Piraeus, pushed by France and Germany, the EU tightened its Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) screening, to limit Chinese strategic acquisitions.

Though China retains control of Piraeus, future acquisitions - for example rail hubs or ports in Italy and Eastern Europe - face greater scrutiny and, on occasion, vetoes.

Thailand: Support for ‘Pro-Democracy Movements’ or Colour Revolution

The NED, USAID, and related fronts have a long history of funding civil society groups, student ‘activist’ organizations, key protest figures and media operations that align with US geopolitical interests.

In the context of the BRI, China sees Thailand as central to its Kunming–Bangkok–Singapore high-speed rail corridor. Political instability, especially youth-led protests and anti-monarchy sentiment, complicate long-term infrastructure commitments.

Although not overtly anti-China, these protest movements are designed to weaken and destabilize key political and elite figures aligned with Chinese infrastructure projects delaying and potentially cancelling them.

Kazakhstan & Central Asia: Stirring Nationalist and Anti-Chinese Sentiment

Western-funded NGOs, media, and think tanks have been deployed at scale to amplify anti-Chinese resentment over land leases, labour practices, and environmental concerns tied to BRI projects.

The NED and George Soros’ Open Society Foundations have been very active in Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. China has repeatedly complained of “foreign incitement” behind anti-BRI protests.

In particular, protests in Kazakhstan in 2019 over rumours of Chinese land seizures and factories were linked by Chinese state media to “foreign interference.”

Ethiopia and Djibouti: Pressure to Undercut Chinese Infrastructure Dominance

China has built key railways, ports, and a military base in the Horn of Africa. Notably the Ethiopia-Djibouti rail and the Addis light rail, and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) base in Djibouti.

In an effort to curb Chinese influence in the region, U.S. and France have increased their military presence in Djibouti, and behind-the-scenes the IMF has been putting pressure on Ethiopian borrowing. The also US quietly discouraged Djibouti from allowing China to expand its military port, citing “debt and sovereignty concerns.”

Montenegro & Balkans: Lawfare and Legal Pressure via EU Channels

China’s financing of Montenegro’s Bar–Boljare highway triggered debt fears as US and EU-linked NGOs and media ramped up the “debt-trap” narrative and pushed local courts to investigate corruption in Chinese-funded deals. Though public-facing, these efforts were part of a wider legal warfare strategy using judicial pressure, ‘anti-corruption’ probes, and anti-China lobbying to forestall BRI progress in Southeast Europe.

Kenya & East Africa: Targeting China’s Narrative with Covert Media Support

China’s investments in Mombasa port, the SGR railway, and telecoms have come under fire in Kenyan media—often citing leaked reports about hidden clauses or sovereignty risks. Several such exposés appear to be sourced from Western-funded ‘investigative’ outfits, including those tied to the Open Society and BBC Media Action. The goal is to shape public perception and turn African elites away from BRI projects.

In general, Western attempts to contain China’s BRI ambitions tend to follow similar trends:

Fronts used: NED, USAID, Freedom House, Open Society Foundations, some Gulf charities (esp. in Balochistan or Myanmar), and religious/human rights groups.

Tactics: Civil society training, covert funding to youth movements, selective media leaks, weaponized transparency, lawfare, and influence over local judiciary or anti-corruption bodies.

Strategic objective: Disrupt or slow Chinese infrastructure deals, delegitimize China’s political partners, and promote alternative funding frameworks (e.g., World Bank, IMF, EU loans).

Transatlantic Alternatives

The Biden administration attempted to propose alternatives to BRI partner countries launching counter-initiatives like Build Back Better World (B3W) and the Partnership for Global Infrastructure and Investment (PGII), in coordination with G7 allies. However, given the ever-increasing weaponization and unpredictability of the US-led financial system and growing consciousness of the predatory nature of Western investment programmes they have been met with mixed results. Western backed/sponsored alternatives include:

Build Back Better World (B3W): Launched by the G7 (U.S.-led) in 2021 to offer transparent, values-based infrastructure finance to developing countries—an alternative to BRI.

Global Gateway (EU): The EU’s €300 billion infrastructure fund aims to redirect African, Asian, and Balkan states away from Chinese funding, with a focus on green energy and digital connectivity.

India-Middle East-Europe Corridor (IMEC): Announced in 2023, this U.S.-backed corridor bypasses China by linking Indian ports through the Gulf (via UAE/Saudi Arabia) into Europe, offering a BRI alternative via rail and sea.

Conclusion

Western efforts to contain the BRI are multifaceted—ranging from covert support for regional unrest (as in Pakistan or Myanmar), political regime shifts (Malaysia), regulatory barriers (EU), to launching counter-initiatives (B3W, Global Gateway, IMEC). While these measures have slowed or complicated some BRI projects, China retains strong momentum in many regions, particularly where Western financing or political will is lacking.